To Stock Market or Not to Stock Market

Dear readers, the time has come! In this article, I share some thoughts on…[*cue ominous music*].... THE STOCK MARKET QUESTION.

This article is about the question: “If I don’t agree with the current economic system, should I or shouldn’t I invest my retirement savings in the stock market?”

This is a big topic! Accordingly, this is a big post. I could have broken it up into multiple shorter posts, but it’s really important to me to have key arguments on both sides of this question all in one place.

Feel free to use the Table of Contents below to skim and/or engage with this as a series of articles - rather than a single monster article - if that works better for you.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback. Thanks for reading!

Table of Contents

The stock market question is on the surface of the iceberg

Reasons TO invest in the stock market, even if you don’t believe in our current economic system:

1. Stock market investing is the easiest and least expensive way to invest

2. Stock market investments are extremely liquid

3. Information is everywhere

4. Stock market returns over the long run may be higher than other investment options

5. You may be able to influence companies via your shareholder power

Reasons NOT TO invest in the stock market if you don’t believe in our current economic system:

1. If you are a shareholder, most things that are good for you personally, are bad for the planet and people collectively

2. Investing in the stock market may mean investing in root causes of problems you are working against in other parts of your life

3. The stock market may not deliver strong financial returns over the next few decades

4. Stock market investments are mostly just vibes

5. Stock market gains entrench inequality

6. Shareholder power may be a red herring for 90% of us

What about innovation?

My personal approach to this conundrum? Rethinking Diversification

The stock market question is on the surface of the iceberg

In some ways, the question: “if I don’t agree with our current economic system, should I or shouldn’t I invest my retirement savings in the stock market?” is THE question that motivated this whole newsletter[1]. But, it has taken me five lengthy essays before I feel like I can even start discussing this. Why?

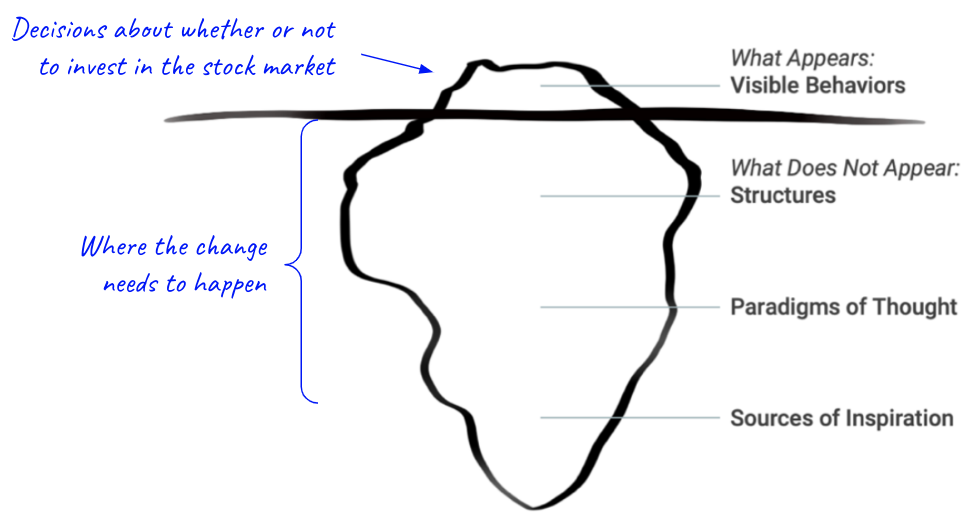

Well, one way to put it is that I’ve come to see “the stock market question” as on the surface of the iceberg of challenges confronting our world today. Like this:

I worry that if we overly focus on questions like “to stock market or not to stock market,” we risk missing what’s below the surface: the structures, paradigms, and sources of inspiration where I believe actual change can and must happen. (Check out the resources at the U-School for more info on these iceberg model concepts).

And yet… the other big reason for this newsletter is that you, and I, and other potential readers all have to make decisions about our personal financial lives based on where the iceberg is today. We may be aware of, and want to participate in, changing the submerged part of the iceberg. AND, we may also recognize that we have to operate on the surface level for many of our own choices, whether we like it or not.

This is why I’ve come to the opinion that, if we are fortunate enough to have some retirement savings but we don’t agree with our current economic system, there is no right answer to the question “should I invest in the stock market?” There is only the best answer for each of us personally. And how we each make this decision for ourselves is, well, extremely personal.

Part of being on the surface of the iceberg of a broken system is that there are many lose-lose choices we are all forced to make, all the time. I think the stock market question is just one example of this. Invest in the stock market, you lose because you are putting your money into a system that is exploiting you and destroying your natural world. Don’t invest in the stock market and you lose because you may have to work longer, possibly in jobs that are exploiting you and your natural world, in order to accumulate “enough” retirement savings. Lose-lose.

Since I believe the decision is personal, I’d like to offer my thoughts about reasons for and against investing in the stock market if you disagree with our current economic system. I hope these can help give you some reflection points to support you in wrestling with this decision for yourself.

Note: Throughout this piece, I use the term “stock market” colloquially. More precise terminology for what I’m talking about would be "publicly traded corporate equities and mutual funds that invest in corporate equities." Another term people often use as a colloquial stand-in for this same concept is “Wall Street investments” or simply “Wall Street.” Feel free to translate to whatever terminology makes the most sense to you[2].

Reasons TO invest in the stock market, even if you don’t believe in our current economic system

Stock market investing is the easiest and least expensive way to invest your retirement savings

Platforms for stock market investing can be extremely user-friendly and inexpensive (although, watch out for hidden fees!). There’s an absolutely massive industry set up to support people in investing their retirement savings in the stock market. So, you can find almost any product or service that you might desire, often at competitive price points.

Want to “set it and forget it” with your savings and investing? Easy. Want to immediately access a wide variety of reports and charts about your investments? Easy. Want a “robo advisor” to do all your investing for you algorithmically and cheaply? Easy. Want to make trades with a single click, on a very pleasing app? Easy. You get my point.

In other words, stock market investing is like the fast food option for investing. Choosing to invest in local and/or community-based alternatives to the stock market can be considered analogous to choosing to buy locally-grown food and preparing your meals yourself when there are many fast food options available. As things stand today, managing community-based investments is usually significantly more time-consuming, and can be more expensive, than “fast food” stock market investing[3].

Some of us have enough going on in our lives that, even though we know that fast food isn’t the best for our bodies or our planet, we still choose it because of ease and cost. This is reasonable! We are all doing our best to survive in a system that is broken. We have to choose our battles. Is managing your savings and investments an area where you want to voluntarily spend more time and resources than you “need” to or not? Only you can determine the best answer for you.

Stock market investments are extremely liquid

Stock market investments are highly liquid, meaning you can enter or exit these investments quickly and easily at almost any time. Compared with many alternative investment options, stock market investments are close to cash in terms of ease of access. That is, if you are invested in the stock market, you can usually access your money almost as easily as if it were in a bank account.

Of course, stock market investments are also completely different from cash in that the value of these investments is volatile. The value of your stock market holdings will go up and down every day, sometimes dramatically. This means that you need to acknowledge the risk that if and when you want to liquify your stock market investments, it could be a very bad time to do so from a valuation perspective.

Nevertheless, if liquidity - the ability to exit your investments quickly - is a requirement for you, stock market investments may be one of your best options to meet this need.

Information is everywhere

You've probably noticed that you do not have to work hard to be surrounded by constant information about what’s going on in the stock market. In fact, you have to work very hard not to be! If you put even a minimal amount of effort in, you can find a virtually endless supply of information about individual stocks and “expert” analyses on the future prospects of the companies underlying these stocks.

Investing is risky. With this in mind, many people have an instinct to want lots of information about the things they are considering investing in. This is a wise instinct! There is no denying that publicly traded companies offer you some of the most standardized and easily accessible financial information out there. In fact, public access to information about a company or fund is part of the very definition of what it means to be a “publicly traded” investment.

Whether or not this information is useful to the average investor is highly up for debate. Believers of the "efficient market hypothesis," for example, claim stock market prices reflect all known information about a company. They would suggest that there is little value for the average investor in attempting to make decisions based on publically available information.

I'm definitely not saying that all the information out there is useful information. I'm saying it's easy to get. If regular access to detailed information about your investments is important to you, nothing will match stock market investments in terms of the ease and quantity of information you can access almost anywhere, almost all the time.

Stock market returns over the long run may be higher than other investment options

The personal finance industry often quotes the fact that, over any 30-year period since its inception, the U.S. stock market has never delivered less than a 7% average annualized return.

Of course, there are reasons to believe history may not be our best guide for our future. A big reason many people do not agree with our current economic system is that they believe the system itself is driving us toward environmental and social collapse, possibly in the next few decades. Even if you hold this view, it’s worth considering that even as the world goes into climate and social meltdown, the stock market could - at least for a time - continue to deliver strong financial returns because the status quo is deeply organized to make this happen.

Historically speaking, it is true that the stock market often delivers very strong financial returns after periods that involve lots of pain for lots of people. Examples include stock market rallies after World War II, the financial crisis of 2008, and the Covid-19 pandemic.

And let me be very clear, financial returns can REALLY matter. The rate of return you get on your savings and investments during your working years can have a dramatic impact on your options in retirement. This is especially true for those who are not in the top 10% of wealth holders.

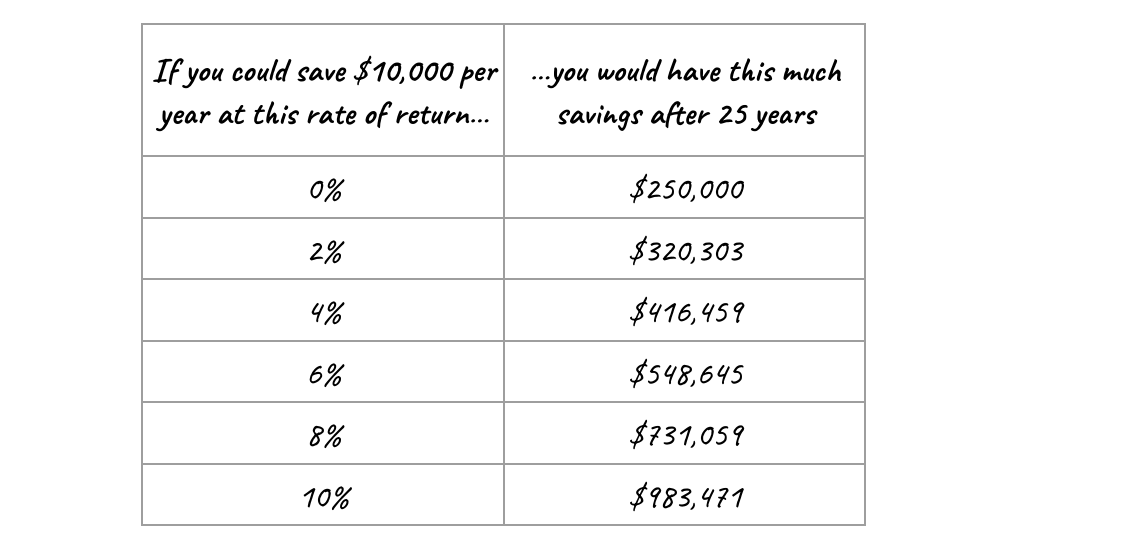

Here’s an example to show how much this can matter. Say you’re 40 years old today and save $10,000 a year for the next 25 years, planning to retire at age 65. If your rate of return on this savings is 0%, after 25 years, you would have $250,000. But, if you were able to get an annualized rate of return of 10% (an unrealistic assumption but one that you can easily find around the internet), you would have… [*drum roll*]… almost one million dollars!

Here’s how the math works out for this scenario with different rates of return:

Compelling “math of the market” like what I’ve demonstrated above is THE reason many people choose to invest in the stock market, even if they disagree with our current economic system. If you believe the market will deliver a rate of return as it has in the past of 7% or more per year over the long run, you may reasonably calculate that the stock market is your best bet for saving “enough” for retirement. Just remember, past performance does not guarantee future results. There is no guarantee that the stock market will return 7% on average in the future. It may be more. And it may be significantly less. It could even be negative.

And yet… if the U.S. stock market really were to go negative over the next few decades, it is hard to overstate how many powerful institutions, systems, and worldviews would be decimated. I personally believe this is the strongest case for investing in the stock market if you are looking for financial return. While returns absolutely cannot be guaranteed, the chances that stock market returns will be decent over the long run are still high because there are many powerful systems and institutions invested in the idea that the market always goes up long-term.

If you are broadly invested in the stock market for reasons related to your retirement savings “math,” you can reasonably assume that there are many powerful forces who are betting on the same math as you. For this reason, I believe that if you’re going to bet on anything making money over the next few decades, the stock market remains one of your best options from a purely financial perspective.

You may be able to influence companies via your shareholder power

Another reason people who don’t agree with our current economic system may still decide to invest in the stock market is because they believe they can use their shareholder power to influence companies to make more “ethical” or “environmentally conscious” decisions.

To what degree shareholder power can and should be used this way is the center of a large debate around so-called “Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG)” investing. I will get into more detail on ESG considerations in my next post. For now, I want to acknowledge that many smart people believe it’s possible to invest in publicly traded companies in such a way as to influence these companies to do better toward environmental, social, and governance goals.

One example of using shareholder power is proxy voting. ESG proxy voting is when you - or an intermediary such as an ESG mutual fund - vote on certain company matters in a way that is aligned with ESG goals. You can only engage in proxy voting if you own shares, and your vote is proportional to the number of shares you own. So, some people who have a large amount of stock market holdings see this as a meaningful way to influence companies in a positive direction.

Another example of how shareholder power can be used for social and environmental goals is by divesting or threatening to divest from companies if they do not take certain actions. This can be an impactful form of shareholder power when combined with movement organizing. This strategy was used effectively, for example, as part of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa in the 1970s and 80s. Just remember, if your main argument for how you are using your shareholder power is “divestment,” then you cannot necessarily count on the math I showed above related to financial returns from the market. You cannot make financial returns on companies you have divested from!

Some people argue that screening out certain “bad” companies and investing in “good” companies is a way to influence all companies to do better. (There is plenty of evidence that your returns can be similar to, or even better than, the overall market when you apply ESG screens in this way.) If you agree with this rationale, the main question then is whether you believe the remaining “good” companies after you’ve applied ESG screens are “good enough” for you. Like everything else I'm mentioning here, I believe that answer will be personal!

Reasons NOT TO invest in the stock market if you don’t believe in the current economic system

If you are a shareholder, most things that are good for you personally, are bad for the planet and people collectively

Returns to shareholders, the core way that your stock market investments make money for you over time, primarily come from companies paying as little as possible for labor, natural resources, and taxes. Returns to shareholders also come from companies promoting consumption and charging the highest prices possible to their customers. This is not due to the people who work at these companies being heartless or evil. This is due to the specific incentives of being a publicly traded company tasked with maximizing returns to you - the shareholder - if you are invested in the company.

Read any stock analysis, listen to any shareholder earnings call, learn some basics of stock evaluation and you will see that it is almost impossible for a publicly traded company to deliver meaningful returns to shareholders other than by reducing labor costs, reducing natural input costs, reducing taxes, and/or by increasing prices to their customers. This is almost by definition what a publicly traded company does. And it is what it must do in order to “pay you” for your investment if you are a shareholder. This is the model. This is the design. It is a feature, not a bug.

You may be tempted to throw up your hands and say, “well, all business works this way, so what difference does it make? If I’m going to invest in anything, it will be extractive of people and planet by nature of being an investment.” While I am sympathetic to this perspective, I strongly believe that the reality is much more nuanced. In fact, I think we are throwing a huge juicy bone to those who advocate a “greed-is-good” worldview when we pretend all routes to profitability are equal.

In reality, there is a lot of diversity in how businesses are run today, have been run in the past, and can be run in the future, while still maintaining profitability. However, the unique incentives of the stock market as it is currently structured specifically exaggerate the most extractive trends of business. You can have the best-intentioned leadership of a company, but if the company is traded on the stock market, its leaders will by design be under massive pressure to consistently show how they are reducing labor costs, reducing natural input costs, reducing taxes, and increasing prices to customers, in order to maximize returns to shareholders. This is a fundamentally different type of pressure than what companies who have a different financing model face.

Financing CAN be set up in such a way that it incentivizes making good decisions for workers, the planet, and the long-term sustainability of the business. But these types of financing models are NOT the stock market as it exists today. (I will be discussing examples of what alternative, less-extractive forms of financing can look like in future posts. You can also find some examples on my resources page here).

Investing in the stock market may mean investing in root causes of problems you are working against in other parts of your life

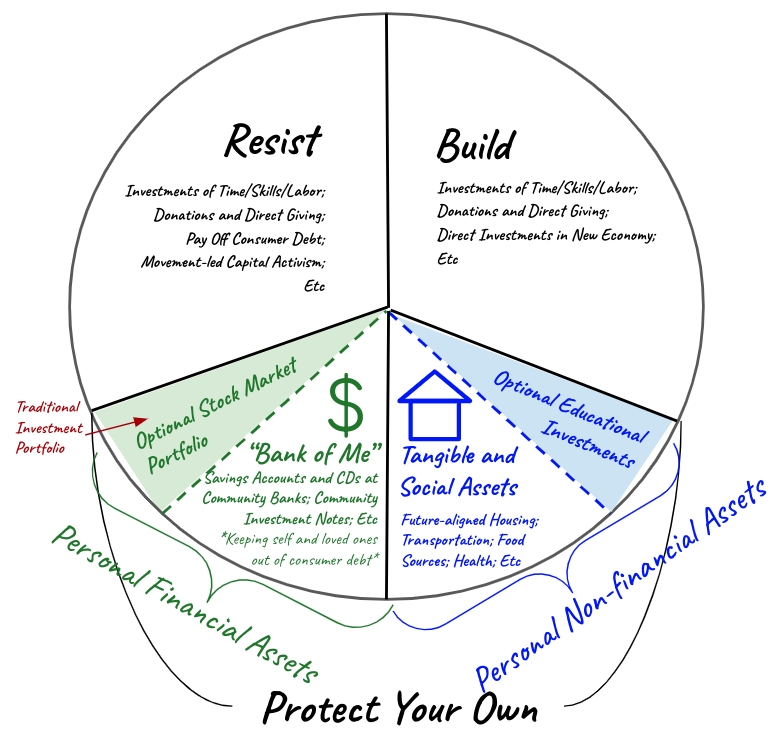

I have previously shared my concept of a peace sign portfolio model. It looks like this:

This is a general framework for those of us who disagree with our current economic system and are interested in thinking about all our investments in our future resource security, holistically. The model suggests that many of us may choose to invest some of our time, skills, and resources into efforts to “resist the bad.” We may consider our "investments" in resisting, or mitigating, some of the worst parts of our current economic system to be investments in long-term resource security for everyone, including ourselves.

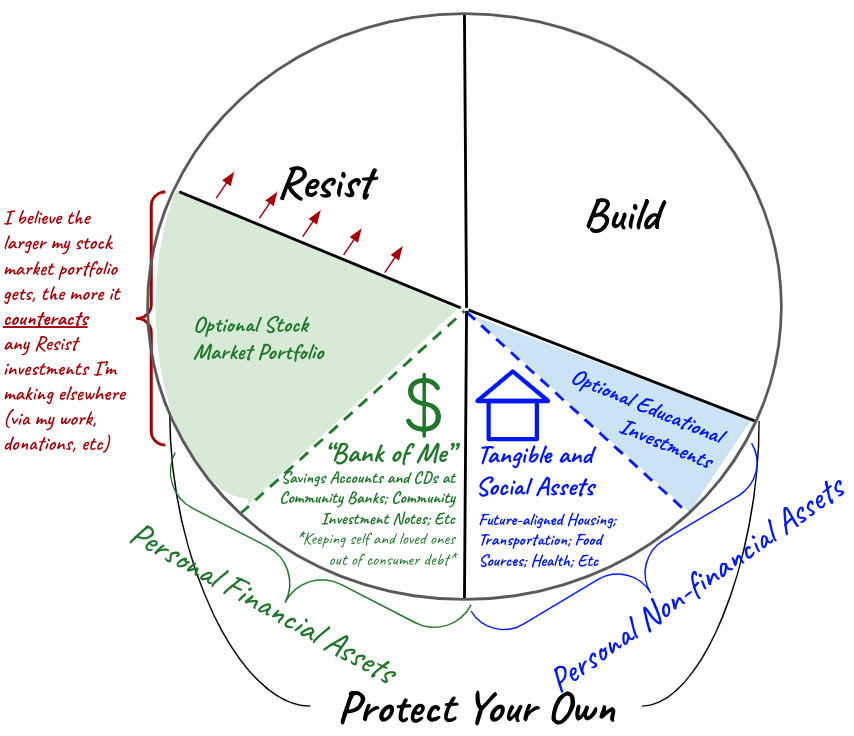

If these ideas resonate for you, you may want to consider whether holding stock market investments could be counteracting other investments you may be making to “resist the bad,” like this:

Shareholder value maximization is THE mechanism that drives our personal financial returns if we are invested in the stock market. When we peel back the layers on many systemic problems facing our communities today, we often find that shareholder value maximization is also a central driver of these problems. For example, shareholder value maximization can be found at the root of problems such as low wages, insecure jobs, environmental damage, and decimated local economies - not to mention the police and prison regimes required to maintain a system with these problems.

If you disagree with our current economic system, choosing to invest in the stock market may feel like voluntarily giving your retirement savings to your enemy to hold hostage. Why would you invest in the very thing you are working against? If you hold this perspective, choosing not to invest in the stock market can be considered a way of maximizing your return on the investments you are making in other parts of your life to “resist the bad” and “build the new” towards a better economic system.

The stock market may not deliver strong financial returns over the next few decades

As I suggested above, it’s highly likely that the stock market will deliver higher returns than other investment options over the next few decades. But there is also a reasonable case to make that it will not.

Some climate scientists suggest we could cross a critical climate destruction threshold as early as 2027. As much as our current mainstream economic theories pretend that business returns are somehow independent from our natural world, many of us recognize that this is obviously not true.

It’s reasonable to expect that no matter how much central banks and other powerful actors intervene, at some point, the wool will be forced en masse from investors' eyes. The market may then drop dramatically to reflect, among other things, the increased input costs and reduced consumer spending capacity that is likely to accompany climate deterioration. It’s impossible to predict exactly when or how this will happen, but it’s not unreasonable to believe that it will happen in the next few decades. If you believe this, there is a case to be made that investing in the stock market is not your best bet, even from a purely financial perspective, given “the writing on the wall” of looming natural (and possibly social) destruction.

Across financial media, you'll often find comments along the lines of: "well, if there's a full-on apocalyptic collapse of our social and economic systems, no investment will be safe. So, the 'rational' choice is to invest in things with a high likelihood of gains if we avoid collapse, such as the stock market." Even if you buy this argument, there are other indicators to suggest that the U.S. stock market may not deliver strong returns over the next few decades. These include historically high valuations across the market today, demographic trends such as an aging U.S. population, and the possibility of increasing global turmoil and war involving the U.S.

For these reasons, it's not inconceivable that the U.S. stock market could be a bad financial bet over the next few decades. Such a scenario is not without precedent. The Japanese stock market, for example, is lower today than it was in 1989.

Stock market investments are mostly just vibes

I find it somewhat ridiculous that most “intro to investing” resources start with a patronizing explanation about what a stock is and what a bond is that goes something like this: “a stock means you own a part of a company” and a “bond means you are lending money to a company.” While these definitions are not technically false, they are basically irrelevant to what retail investors (you and me) are actually doing when we buy or sell a stock or a bond, or more commonly a mutual fund or ETF composed of many stocks and bonds.

Unless you are an institutional investor or extremely wealthy, all of your stock market investments are on the secondary market. This means that the “ownership” has already been sold for the company (in the case of stocks) and the money has already been lent to the company (in the case of bonds). When you buy and sell stocks or bonds, you are mostly just taking part in passing around digital pieces of paper that represent these ownership stakes or loans. And, the main thing you are doing, the main thing everyone is doing in the stock market, is betting on how much other investors will be willing to pay for these digital pieces of paper in the future.

In other words, it is an enormous stretch of the imagination to pretend that the best explanation of what you are doing when you invest in the stock market is owning pieces of companies. It would be much more accurate to describe what you are doing as betting on what future investors will pay for whatever digital pieces of paper you are buying. And the main driver of what other investors will pay is what they think future investors will pay.

Therefore, it is more honest to recognize that most people’s stock market “investments” are simply digital bets on future vibes of the stock market, albeit nicely packaged for you by layers of financial intermediaries[4]. Of course, this explanation makes the whole stock market thing fit uncomfortably with our collective mythology that our investments are “fueling our economy,” so I understand why this is a less popular explanation. But, that does not make it less true! If you are not particularly excited about investing in vibes, if you’d rather invest in something more closely related to the “real economy,” you'll likely need to look beyond the stock market as it exists today.

Stock market gains entrench inequality

Above, I talked about the “math of the market.” In that case, I was talking about the anticipated long-run rate of return being a key reason many people choose to invest in the stock market. Remember that math is theoretical. We do not know what future market returns will be. Now, I want to talk about another form of market math: the math of market ownership.

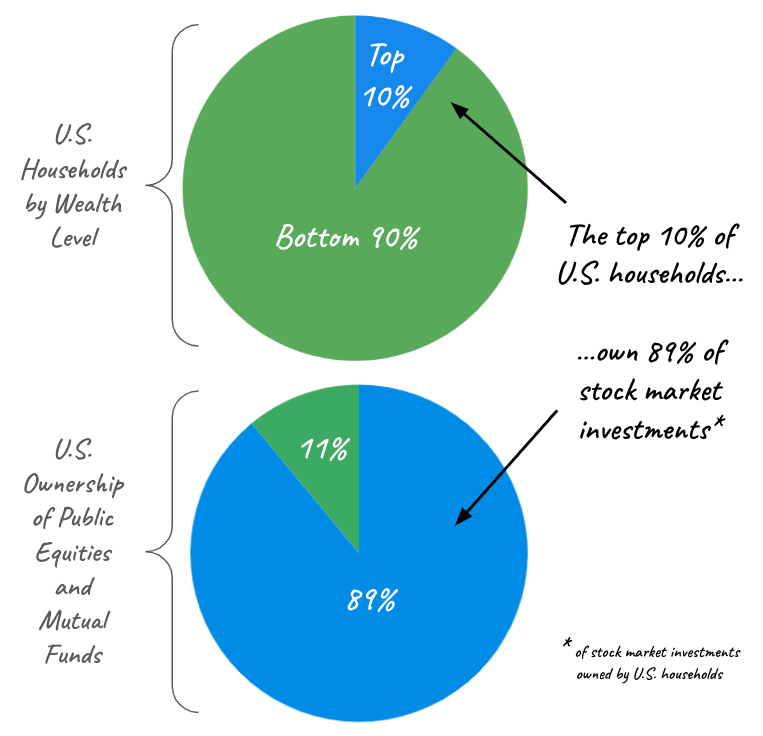

As of Dec 2022, the top 10% of wealth holders in America owned 89% of stock market investments. No, that is not a typo, here’s the data. These stats can be visualized like this:

If you hold a diversified portfolio of stock market investments today, when your personal investments go up, wealth inequality increases. Period. Whether or not you agree that this is fair or right, this is what happens.

Here's an example of how it works: if the stock market goes up $1,000, the top 10% shares an $890 gain and the bottom 90% shares a $110 gain[5]. Don't like it? Sorry. That's just the math of market ownership.

If your personal values are at odds with the extreme level of wealth inequality in the U.S. today, you may feel that holding stock market investments is in direct contradiction to your values. While I’m not advocating this, it’s mathematically true that if the stock market were to fall dramatically, levels of wealth inequality would go down. (I'm not advocating this because the poor and middle class would still likely suffer the most. The U.S. experienced an extreme case of this dynamic in the 1930s, for example.)

A reason you may choose not to invest in the stock market may be to avoid tying your financial resources to a system that can only increase gains to you individually by also increasing wealth inequality collectively.

Shareholder power may be a red herring for 90% of us

I mentioned above that one reason some people choose to invest in the stock market even if they don’t agree with our current economic system is because they believe they can use their power as shareholders to influence companies. If you are in the top 10%, and particularly if you are in the top 1% (who alone own 53% of the stock market), this may be true IF you actually use that power (more on that in my next post).

If you, like most Americans, are not in the top 10% of wealth holders, it takes a lot of imagination to believe that you have any meaningful “power” via your stock holdings. Just look again at the pie chart visuals above. If every single person in the 90% who holds stock market investments were to work together, their collective power as shareholders will still only be as big as the small green 11% pie slice. And, this 11% pie slice of theoretical “shareholder power” would likely be further diluted by the intermediaries that most people in the 90% must use to be invested in the market.

Am I saying that the 90% does not have collective power to influence large companies traded on the stock market? No. Definitely not. I’m saying this group does not have very much power as shareholders. And, I believe pretending that we do may keep us distracted from engaging more effective strategies for change.

While the 90% may not have significant power as shareholders, this group - being the 90% - represents the majority of workers, consumers, and voters in the U.S. As such, this group has very real power to create systemic change if and when we organize around almost any group identity other than as shareholders. Recognizing this, it’s easy to see how those who favor keeping our economic status quo the way it is would prefer the 90% to believe their best avenue for “impact” is through shareholder power[6].

What about innovation?

Some people might read all this and say: what about innovation? Shouldn’t it be true that a key way investors get returns from the stock market is from companies “innovating” to “provide value” to society? To that I say, yes! It should be that way, at least according to capitalist utopian ideals. And, I surely wish it were that way in reality because then I wouldn’t have had to write this long-winded article! Instead, we could all just go forth to happily invest in the stock market and know that our investments were simultaneously providing us a financial return and making the world better off through the magic of innovation. Wouldn't that be nice?

Unfortunately, I see very little evidence to suggest there is a strong relationship today between shareholder value maximization and innovation that provides value to society collectively. I think the relationship between shareholder returns and good-for-the-world innovation is especially weak when it comes to publicly traded equities. But, reasonable people disagree on this point.

It is certainly true that the idea of “innovation providing value" is at the heart of most moral arguments in favor of our current shareholder-value-oriented financial system. You will find this case made almost anywhere (else) you look for why you should invest in the market and why you “deserve” a financial return on your investments. My guess is that if you have read this far, you are not particularly convinced that the stock market is good at aligning profit with innovation that’s good for society. Still, I recognize that according to theories of how capitalism should work, this is a point worth considering.

If you are interested in the debate about the role of the market in promoting innovation, I’d highly recommend reading and following the economist Mariana Mazzucato. Her research shows, among other things, how many socially important innovations have come from government-funded projects (examples include the internet, GPS, and many important medical advancements). She also shows how “the market,” as we have structured it today, actually keeps vast amounts of useful innovation from being well-used by society due to strong incentives to hoard patents and to charge prohibitive prices for otherwise socially valuable innovation such as pharmaceuticals.

I’ll grant that maybe, here and there, there are publicly traded companies that are able to deliver returns to shareholders by adding value through innovation. However, in my opinion, this added value is offset by the negative value - also created by the stock market - that keeps “good” innovation from being well-used by society. And, don’t even get me started on the many "financial innovations" that have absolutely proven to be net value-destroying for society!

For these reasons, when it comes to the innovation argument, I personally land on “neutral.” I think it’s neither a clear case for, nor a clear case against, investing in the stock market broadly speaking. However, it’s an argument people often feel strongly about, so it’s definitely worth considering where you fall.

My personal approach to this conundrum? Rethinking Diversification

My personal response to the conundrum of the stock market question, at least for now, is to focus on building a portfolio that feels truly diversified to me. My version of this is represented by the “peace sign portfolio” model that I shared above (which I discuss in more detail in this article).

In the interest of diversification, I’m choosing to keep some of my investments in the stock market, particularly anything related to an employer retirement account match. But, I’m certainly not thinking of my stock market portfolio as all, or even most of, the way I’m investing in future resource security for myself, my family, and my community.

Specifically, I’m actively looking for opportunities to expand my portfolio by making investments in “build the new” categories outside of the stock market. And, I recognize that the larger my stock market portfolio is, the more I may be off-setting and counteracting the impact of any “resist the bad” investments I may be making in other parts of my life.

I definitely dislike the feeling of holding some of my retirement savings "hostage" in the stock market while I'm simultaneously investing in resisting aspects of our economic system that are exacerbated by that same stock market. Even so, I’ve concluded that for now, holding some (but certainly not all) of my savings in public equities is the best compromise for me and my family when I’m honest about the lose-lose choices I’m faced with on the surface of our economic “iceberg” today.

Most importantly, I'm trying to actively avoid investing in the idea that I will be better off if my stock market investments go up at the cost of collective wellbeing. I want to set myself up so that I'd be fine with seeing my stock market investments decline or stagnate if this means collective resource security is significantly improving. I believe this could be possible IF we can change our systems and paradigms. So, I plan to prioritize investing in "resisting the bad" and "building the new" to hopefully play my little part in pushing our collective iceberg toward something better for all of us.

What might these “build the new'' investments look like? Exploring that question will be an ongoing focus of many of my future posts (feel free to check out my resources page if you’re curious about examples now).

First, I suspect some people may be wondering: “If I DO decide to invest in the stock market, what about this ESG stuff?” My thoughts on that are coming up next.

Footnotes:

[1]

In this article, I'm considering "the stock market question" specifically for those who have a long time horizon for their investments: at least 10 years, ideally multiple decades. Please note that many of the reasons I've listed in favor of stock market investing would not hold for those with a shorter time horizon.

[2]

When I use "stock market" in this article, I'm also primarily referring to the U.S. stock market. Many of the arguments I make on both sides of the stock market question would also apply to stock markets in other countries. However, there are also important differences across different jurisdictions that I do not explore here.

[3]

Shout out to Marco Vangelisti for this fast food analogy. Marco makes the point that developments around our food systems provide a good analogy for investing. Over time, we have made feeding ourselves more convenient with things like fast food and TV dinners. But now, many of us are recognizing that this convenience comes at a cost to both our bodies and our planet. We now realize that our personal and collective health depends on making choices that are more inconvenient than fast food, like buying local food and cooking for ourselves. Might a similar trend be emerging with investing?

[4]

A standard assumption in finance theory is that stock prices are based on "rational" expectations of future sales, profits, and cash flows of publicly traded companies. Lots of ink has been spilled among finance academics and professionals about whether or not this assumption holds in the real world. Certainly, there's lots of evidence of the market behaving "emotionally" and "irrationally" - in other words, being driven by "vibes." Still, I acknowledge that, in theory, market prices are supposed to reflect the value of a company's future cash flows. Whether or not this assumption still sometimes holds today is yet another personal judgment that I'd encourage you to make for yourself.

[5]

This is a stylized example. It is not exactly like this because I’m looking just at U.S. stock market ownership and American household data. A lot of U.S.-listed public equities are owned by foreigners and a lot of Americans hold foreign equities. Even so, the basic dynamics still hold: when the stock market goes up, wealth inequality goes up due to the math of market ownership.

[6]

Again, I'm talking about the bottom 90% of wealth holders here. I'm trying to point out that most Americans - 90% of U.S. households - may not have as much shareholder power as some marketing materials for "responsible" investment products suggest. On the other hand, if you happen to be in top 10% of U.S. households by wealth, there is absolutely a case to make that you have shareholder power, possibly significant amounts. I will discuss this further in my next post.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Marco Vangelisti's course, "Toward Aware and Values Aligned Investing," for helping me work out and solidify my thoughts for this article. Check out Marco's upcoming courses here:

The following resources inspired the "peace sign portfolio" model that I referenced in this piece, also discussed in more detail here.

📙 Social Movement Investing, by Ariel Brooks, Libbie Cohn, and Aaron Tanaka of the Center for Economic Democracy

📘 Put Your Money Where Your Life Is, by Michael Shuman

📗 The Resilient Investor, by Hal Brill, Michael Kramer, and Christopher Peck

While the above resources inspired my thinking for this article, any errors in logic or facts are my own.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.