Rethinking a Balanced and Diversified Portfolio

In this article, I share an example of how we might think about a "balanced and diversified" portfolio from a community-minded personal finance perspective. This model is inspired by concepts from the The Resilient Investor and from a white paper on Social Movement Investing from the Center for Economic Democracy.

This is essay #2 in my series on topics related to community-minded personal finance, ICYMI here's essay #1.

What we use as our starting place can make a big difference in how we are able to engage with various topics in personal finance.

In this post, I want to talk about concepts related to a "balanced and diversified" investment portfolio. And, I want to share some ideas for a different starting place to think about these concepts from a community-minded finance perspective.

First a note: If you are following my articles chronologically, you might notice that I’m jumping ahead several steps by talking about investments right away. Most of us have many steps along our personal finance journey before we're ready to discuss investments. If investing is currently the last thing on your mind related to your personal finances, you may want to skip this article for now. You can always come back to it later.

What is typically meant by a balanced and diversified portfolio?

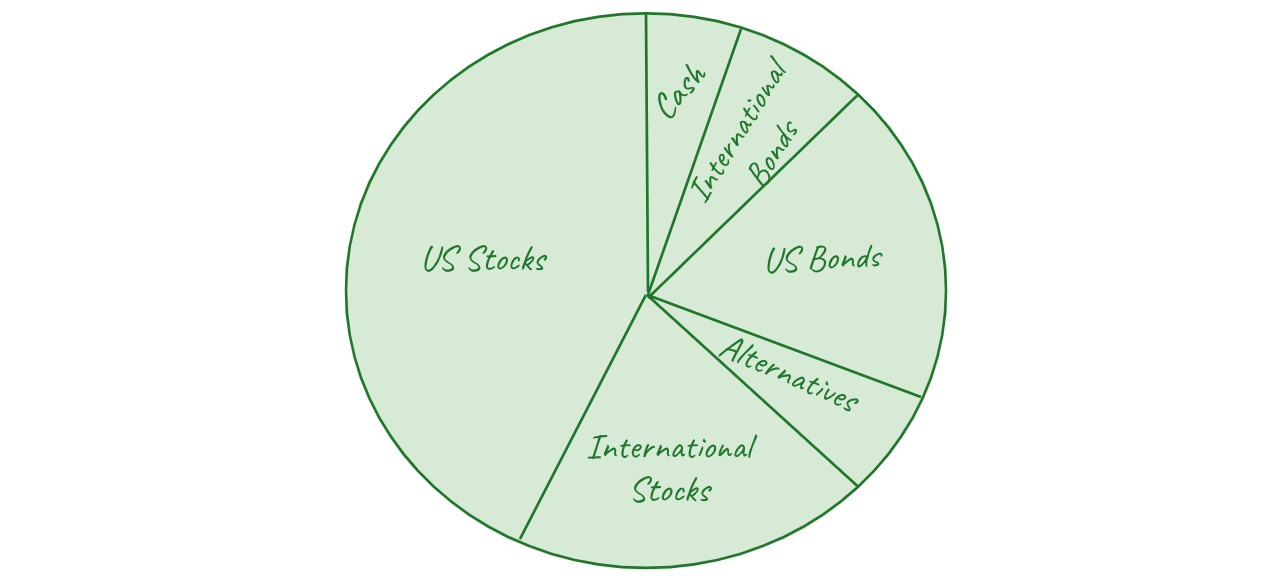

From the perspective of status quo personal finance, a balanced and diversified investment portfolio might look something like this:

A portfolio like this is considered "diversified" because it has a mix of different types of stocks and bonds, and presumably many different individual stocks and bonds within each of these types. A portfolio like this would be considered "balanced" if it is "optimized" for your personal "ability and willingness to bear risk."

From a traditional finance perspective, the moment you start discussing investments, the words "diversified," "balanced," "optimized," "risk" and even "ability and willingness to bear risk" are not only already defined, but their meanings in relation to you personally are largely predetermined.

Here's how:

Studies repeatedly show that - on average, over time - you cannot "beat the market" by individually picking stocks and bonds. Therefore, the general consensus is that the best approach to investing is through a well-diversified portfolio.

Modern Portfolio Theory ("MPT"), which was developed by economists in the 1950's, is the standard starting point today for determining how to build a "well-diversified portfolio." MPT suggests that there's a formulaic way to diversify a portfolio in an optimal way to maximize your expected returns for any given level of risk. But, risk is very narrowly defined in MPT as "the volatility of portfolio returns." Since most real human people cannot just tell someone what their preferred "volatility of portfolio returns" is, everyone has basically agreed that we can compute this by determining your willingness and ability to bear risk (also called your "risk tolerance" or "risk profile").

In other words, for me to create an optimally balanced and diversified portfolio for you, I just need to know your willingness and ability to bear risk. The rest is largely determined by a formula.

We can pretend that willingness to bear risk is a big part of an individual's investment decisions, but in reality what matters most, for most standard portfolio construction, is ability to bear risk, i.e. do you have either a) a lot of time until you need to draw on your investments; or b) a lot of money? If the answer is yes to a or b, you have a high ability to bear risk, otherwise it's low.

I share all this not to pick a fight with MPT. I share this to point out that, if we begin with this general framework as our starting point, the outcome of any discussion about what "risk" or "balanced" or "diversified" or even "willingness and ability to bear risk" means for you is mostly already determined. And, it is already determined in a way that is highly depersonalized.

I think that we have a lot to gain from broadening our perspective so that we can actually engage personally with these concepts - we are talking about personal finance after all.

But how might we even start?

My personal definition of “financial responsibility”

I mentioned in my last post that one place to start when taking a community-minded approach to personal finance is by considering our own definitions of “financial responsibility.”

While it’s always shifting a little, my personal version of financial responsibility goes something like this:

Be smart with money, but don’t let it rule your life. Don’t be greedy, but be careful and prepare for the future. The goal is not to have money for money’s sake, the goal is to have resource security for myself and my family. And, to be able to be generous within my community and beyond.

In addition… I also see myself as having certain financial responsibilities related to my specific context within systems of power and privilege. My personal context is that I am a mid-to-upper-middle-class white lady in America, with multiple degrees, no student debt, and I own a home with my partner. Although my ancestors were poor farmers, as a student of history, I know that I have benefited from generations of systems that discriminated against (and outright stole from) Indigenous, Black, and Brown communities. I recognize that unjust and racist systems play a role in my current relative socioeconomic privilege. Therefore, a part of my personal definition of financial responsibility includes directing resources toward efforts addressing systemic injustice, specifically efforts that are led by BIPOC communities.

Not only do I care about addressing systemic injustice because I think it’s the right thing to do based on my personal context, I also believe that my own goals of resource security for myself and my family benefit from this. Between trends toward both climate meltdown and social meltdown, I am anxious about general resource security in my community and larger communities around me in the future. For me, part of fulfilling my financial responsibilities to my son (who’s currently 3 years old), and to future generations, is to direct resources toward efforts working to reduce the risk of climate and social calamity. I personally do not believe we can reduce this risk meaningfully without significant systemic change in the direction of both ecological sustainability and increased justice for historically oppressed communities.

I’m sharing my definition of financial responsibility here because, as I have mentioned, I believe community-minded personal finance assumes everyone has their own subjective definitions of financial responsibility. I expect yours will be different from mine (it should be!), but I hope that knowing some of the angle I’m coming from can help you translate the rest of this article in whatever way is most useful to you based on your context.

Other ways to think about a balanced and diversified portfolio

What might a model for a balanced and diversified investment portfolio look like that could accommodate a definition of financial responsibility along the lines of what I just shared?

To get to an answer, I drew on the following three excellent resources:

1) Social Movement Investing, by Brooks, Cohn and Tanaka from the Center for Economic Democracy

2) The Resilient Investor, by Hall, Brill, and Peck from Natural Investments

3) Put Your Money Where Your Life Is by Michael Shuman

These are each awesome examples of community-minded approaches to investing in their own right, and you should check out any of these that look interesting to you.

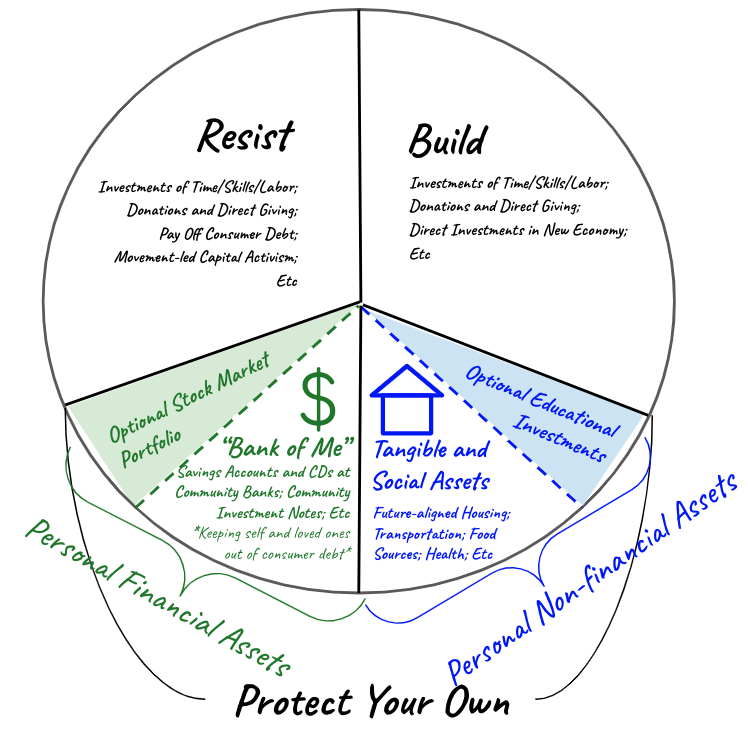

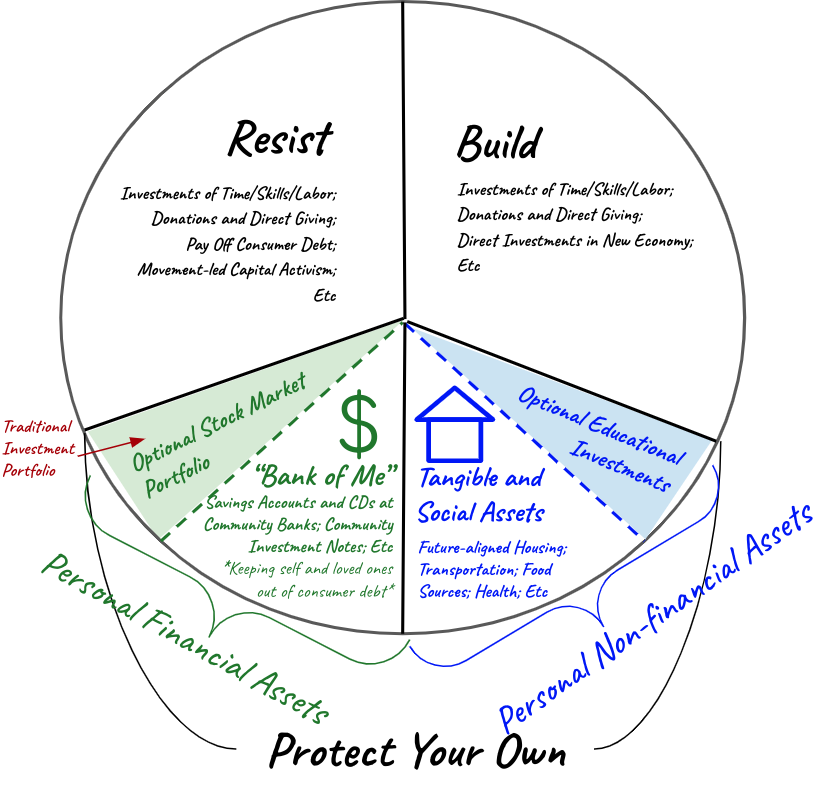

Combining ideas from the above three resources led me to develop the following alternative model of a balanced and diversified investment portfolio:

A peace sign investment portfolio model

While this model is guided by my personal definition of financial responsibility that I shared above, I’m offering it as a general model for you to use as a different starting point for thinking about what "balance," "diversification," and "risk" might mean to you in the context of your personal investment portfolio.

I call this a "peace sign portfolio model" because I'm cheesy like that and because the peace sign shape represents a "balance and diversification" that makes sense to me, aspirationally. Your version of "balanced and diversified" might look very different, so feel free to call it whatever you want!

This portfolio model has three main sections: Resist, Build, and Protect Your Own. While the lines are blurry, I see the Resist and Build sections as representing investments in collective systemic change, and the “Protect Your Own” sections as representing closer-to-home investments that you benefit from directly.

Of course, the definition of “Protect Your Own” will mean different things to different people. I think this definition should be completely open for you to choose what this means to you. "Your Own" could mean, for example: 1) just you, or 2) your immediate family, or 3) your chosen family, or 4) a wider community of loved ones. The point is that it is a “unit” that is smaller and more close to you, personally, than “the collective.” For me, it means my partner, my son, and to some extent our immediate family and circle of loved ones.

I consider all these sections - Resist, Build, Protect Your Own- as interrelated. Exactly how they are interrelated will also be personal to each of us. For example, if you identify as coming from a low-income background, I can imagine that you may see any act of “protecting your own” as investing in “resisting and building” and feel that there is no distinction at all among these categories. That view makes sense too! The point is: yes it’s personal, yes it’s contextual, but we absolutely CAN think in a more community-minded way about what a diversified and balanced portfolio might mean to each of us based on our specific context.

What makes this approach different from the traditional finance view? A lot of things!

In future posts, I’ll get into the details of each section and how they interact. For now, let me point out the biggest differences this model suggests for how we might think differently about a balanced and diversified investment portfolio.

Top ways this approach to “balanced and diversified” is different

1) First, this approach zooms out to take a much broader view of what we consider an investment portfolio. In fact, the entirety of the traditional investment portfolio I started this article with is represented here as just the single light green "optional stock market portfolio" piece of the pie.

This portfolio model suggests that we can consider any use of our resources, including our time, skills, and labor, as an investment. And, we can consider non-financial assets, including tangible assets like our housing and less tangible things like our health or education as part of our investment portfolio.

Hal Brill, Michael Kramer, and Christopher Peck make a strong case for this type of wider perspective on investing with their Resilient Investing approach. If you are interested in this idea, you should definitely check out their book. They’ve also made many of the models from their book freely available. I especially recommend their Resilient Investor Map here and their concept of personal future forecasts here.

2) Second, this peace sign portfolio model attempts to align personal investments with the perspective that systemic change is critical to collective long-term resource security. The Resist and Build sections of this model represent two key aspects of working for a more sustainable and just future.

"Resist and build" strategies have a long history in social movement work, but I want to give huge appreciation to the Social Movement Investing white paper by Ariel Brooks, Libbie Cohn, and Aaron Tanaka and the Center for Economic Democracy for the notion of applying this to investments. The Social Movement Investing white paper also introduced me to the Just Transition framework developed by Movement Generation and Climate Justice Alliance.

I find the Just Transition framework to be a very helpful starting point for describing the kind of systemic change I personally want to be working for. Among other things, it points out that "transition is inevitable, justice is not" and that in order to transition from an "extractive economy" to a "living economy," we need to do so in a way that prioritizes strategies that "democratize, decentralize and diversify economic activity." Importantly, in order to pursue a Just Transition, we will need holistic, wide-ranging societal work both to "resist the bad" and to "build the new."

I like thinking of these concepts of Resist and Build in the context of what a theoretical "balanced portfolio" of investing in collective impact might look like. For those of us who believe that systemic change is required for humanity - and the natural world we depend on - to thrive into the future, it makes intuitive sense that we will need people and resources committed to both resisting and building to get there. We recognize that if we collectively become out of balance and swing too far towards only resisting, or only building, our chances of a successful transition are exposed to increased risk.

The Social Movement Investing white paper is excellent for outlining an approach to investing that avoids the trap of weak solutions by focusing on movement alignment and community power-building. But, a lot of the white paper discussion is oriented toward institutional investors or wealthy "impact investors." If that’s you, I could not recommend it more as a starting point (in fact, if that’s you, please ignore the rest of this article and refer to the Social Movement Investing model instead!).

For those of us who are not institutional investors, or wealthy impact investors, one of the implications of the Social Movement Investing white paper is that despite the promises of "sustainable" finance, there is not an “easy button” for investing in a way that strongly supports a Just Transition. The authors make a compelling case for why simply screening out certain stocks and bonds from an otherwise traditional investment portfolio is just not going to get us there.

3) But, there are plenty of other ways non-wealthy people can still "invest" in Resist and Build strategies. This is the third key point I am trying to offer with the peace sign portfolio model. Even if, for example, we do not have assets to divest from “bad” companies as part of a broader social movement, we absolutely still get to “count” how we spend our time, skills, and labor as a key part of how we “invest” in making our world a better place.

Furthermore, this model helps us see how there are some clear ways where personal finance goals related to "protecting your own" and "resisting the bad" are especially aligned. Specifically, I think that paying off consumer debt and building a meaningful personal cash savings fund (often called an "emergency fund"), can be considered an important "impact investment."

In his book, Put Your Money Where Your Life Is, Michael Shuman calls this building the “bank of me.” He points out that building up a fair amount of cash savings can deliver a theoretical financial return if it helps you avoid credit card debt and/or give loved ones a loan to pay off their credit card debt. I like this terminology because it reminds us that avoiding consumer debt and investing in our own cash savings not only increases our personal resource security, but also helps “starve the beast” of an extractive financial system that preys on people in financial crisis.

4) Fourth, this model attempts to highlight that how we define our "investments" in all these categories is highly personal. If these concepts of "resist the bad" and "build the new" resonate with you, I invite you to think creatively about what "investing" in these looks like for you based on your specific life circumstances and your "resources."

For example, maybe you see investing in your personal self-care as a form of "resisting" and providing care for family members as a form of “building the new.” Or maybe your job or your business is related to resisting, or building, or both. Or maybe your art or your healing or your volunteer work is related to resisting, or building, or both. My point is, we all get to define these categories for ourselves. And, for those of us interested in "investing in a better world," so-called financial "impact investments" are far from the only way of doing this.

In other words, YOU get to determine what investing in a better world means to you. I promise your definition will be just as good as, likely better than, most finance professionals'.

5) The fifth and last overarching point I want to make with this model is that for those of us who have some financial resources, and want to support just social change, movement-aligned donations and direct redistributive giving to individuals must not be forgotten as very important ways to support the work.

When going down the rabbit hole of trying to align our finances with our values, it is critical to keep in mind that we are not going to “invest our way out” of things like racism, poverty, inequality, and climate destruction. We just obviously aren’t! Please do not trust anyone who is telling you we can solve issues as complex as these with finance alone!

Even so, I think we can and must do better as a society to push our finance systems away from causing the destruction of our social and natural world that they have caused to date. This work will absolutely require people and organizations with significant financial assets to adopt better frameworks, like those proposed by the Social Movement Investing model.

And, I believe that those of us with some resources, even if we are not on the very top end of the wealth distribution spectrum, also have a role to play. Allowing ourselves to think about what a truly personalized version of a "balanced and diversified" investment portfolio might look like to us is one place to start.

Start with a blank piece of paper. Draw your own ideal investment portfolio. Include the Resist, Build, and Protect Your Own sections if these feel right to you. Indicate the balance that you want to aim for with your personal resource investments (use a time period that is meaningful to you). Add additional details or "pie pieces," as you see fit, to represent your version of an ideal "balanced" portfolio.

Next, consider how near - or far - your current resource investments are today from the ideal model you've just drawn. No need to get overly precise, just think about what stands out for you when you think about this. Are there areas where you feel aligned and on track towards your ideal resource investment balance? Are there areas where you feel far off from your ideal resource investment balance? What ideas does this exercise bring up for actions you want to take next?

Thanks for reading! Here are some resources that influenced my thinking in this article:

The Next Egg - A network and resource library "reimagining retirement savings and investment"

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.