ESG and Me

Do you disagree with our current economic system? Do you have some savings that you’ve still decided you will hold in stock market investments? Are you wondering how to think about all this ESG hubbub in relation to those investments? If you answered yes to these questions, this article is for you! (And if you answered no to any of the above, skip this one!)

Table of Contents

My summary overview of ESG

Top problems with ESG

Can ESG help?

ESG is not free

Investing costs 101 explainer

Deciding if you want to pay for ESG

If you’re in the 90%, rationale for NOT doing ESG

If you’re in the 90%, rationale FOR doing ESG

If you’re in the top 10%, rationale for NOT doing ESG

If you’re in the top 10%, rationale FOR doing ESG

Getting started with ESG

So, you’ve thought about it. You’ve weighed the pros and cons. Even though you disagree with our current economic system, you’ve decided the right choice for you is to hold some of your retirement savings in public equities (what I’ve been simplistically referring to as “the stock market”). Now you’re faced with another decision, should you “do ESG” with your stock market portfolio or not?

In this article, I’ll do my best to give you some clear points of reference for making that decision for yourself.

Before I start, I want to note that this article assumes that you have read these two previous posts of mine:

If you haven’t read those articles yet, I’d recommend you check them out first.

My summary overview of ESG

As much as it pains me, I can figure no other way to start this discussion other than by acknowledging what a bordering-on-meaningless sh*t show of a subject ESG has become here in 2023. This is partially due to the fact that ESG is one of the latest amorphous acronyms that has “stuck to the wall” from the fear-mongering spaghetti being thrown there by certain you-know-whos. And, it is also true that ESG (which stands for “environmental, social, and governance” investing) had a number of fundamental problems even before it got caught up in recent pop-political culture wars.

I should explain right now that, in consideration of article length, in this post I will not be fully diving into all the problems with ESG. If you're looking for a more thorough and nuanced take on the complexities of ESG, let me recommend this article by Elizabeth Pullman and this article by Kate Aronoff.

Still, I need to frame up this discussion with some explanation of what ESG is, which means I can’t avoid discussing some of the fundamental problems with ESG. This is because one of ESG’s main problems is the very definition of "ESG" itself.

Top problems with ESG

Here are two of the biggest problems with “ESG” as I see them:

- What “ESG” means is unclear and contested. The three ESG categories - environmental, social, and governance - are extremely broad. This leaves room for a wide range of interpretations of exactly what each category means, not to mention all three lumped together. There are many efforts attempting to standardize definitions and metrics for each of the E, S, and G categories, but because the categories are SO broad, the whole field is highly vulnerable to power and politics playing a central role in the definitions and metrics themselves. This has led, in many (but not all) cases, to major watering down of the potential impact that a focus on these areas could have.

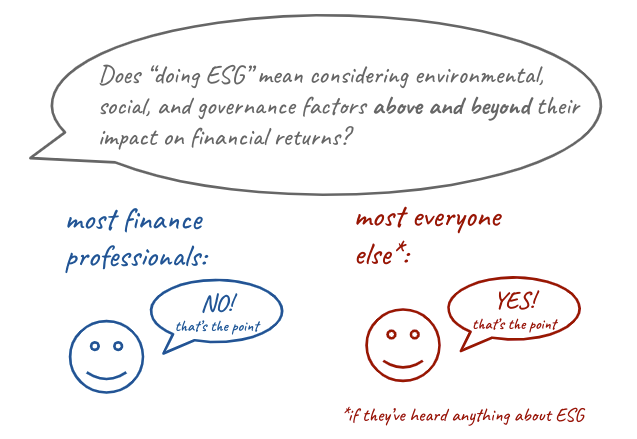

- What it means to “do” ESG is unclear and contested. There is a gaping divide in how certain groups define what it means to do ESG in relation to financial considerations. There’s a large camp, primarily among finance professionals, that considers the whole point to be that ESG factors are considered ONLY to the extent that they are related to improved financial outcomes. In this view, considering environmental, social, and governance factors is simply good investing. Meanwhile, almost everyone else uses “doing ESG” to refer to investment strategies that specifically consider environmental, social, and governance factors above and beyond how they relate to financial outcomes.

In other words, if you ask how ESG relates to financial returns, you could get exactly opposite answers depending who you ask, like this:

In my opinion, these problems are symptoms of the bigger underlying problem that, at its core, ESG is based on un-examined old-school economic assumptions. But that’s a story for another time (a story that motivated this whole newsletter, as I explained here).

Since issues related to the definition of ESG are a big part of the can-of-worms that is ESG in the U.S. today, let me clarify how I'll be using "ESG" for the remainder of this article. I use “ESG” to refer to any public markets-based investing strategy that either: 1) considers any kind of “environmental, social, and/or governance” risks in companies; or 2) seeks to influence companies to pursue any kind of “environmental, social, and/or governance” goals. I consider “socially responsible investing,” “sustainable investing,” or any other type of “ethical” investing strategy that is applied to publicly traded securities as falling under the umbrella category of “ESG” today [1].

Is this still a broad and blurry definition? Yes. But, what can I say, that’s ESG.

Can ESG help?

There’s a lot of great content already out there that digs into how and to what extent ESG may be a useful approach to addressing key problems facing our world today (see, for example, these same two articles I referenced earlier here and here).

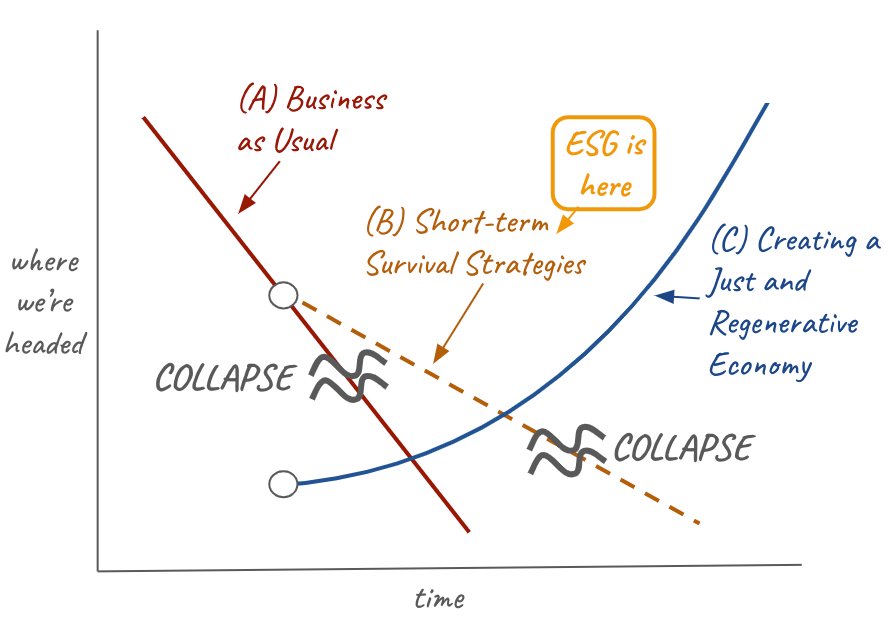

In this article, I’m going to keep it simple. Here’s my quick and dirty visual summary of where I think ESG lands in the scheme of possible solutions to our biggest social and environmental problems today:

Above, the “Business as Usual” Line (A) is a representation of our current trajectory. Various ecological indicators suggest that without significant changes, we are rapidly approaching environmental collapse on a global scale. In the U.S, social indicators also suggest we are headed towards multiple forms of social collapse if we continue with business as usual. Taking just one example, if current trends continue, median wealth of Black American households is on a trajectory to reach ZERO DOLLARS in the next few decades.

I believe that ESG is a decent tool in our toolbox to get to the “Short-term Survival Strategies” depicted by Line (B) above. In other words, I think that if ESG is done well (more on this later), it really could help extend our timeline before we reach various forms of general collapse worldwide [2]. As shown, this extra time we could gain from moving to Line (B) could be extremely valuable. But, we need to recognize that solutions like ESG alone are not going to get us to the “Just and Regenerative Economy” Line (C) that we ultimately need.

In my opinion, the biggest risk with ESG is that it may play the role of distracting us or soothing us into complacency so that we don’t build Line (C). That would be a big problem.

While I recognize that the above diagram is highly simplified, I hope it helps clarify how ESG is what we might call a "classic both/and situation." I believe it’s true that ESG is not enough and may even be a dangerous distraction from very important work that needs to happen in our economy. And, I think it’s also true that ESG done well could play an important role in moving us toward a better collective future. Importantly, I think reasonable people can and should disagree about where ESG falls on this diagram. Where you think it falls will likely play a big role in how you choose to use ESG, or not, for your investments.

ESG is not free

Ok, so let’s say you take my point that ESG has problems and it’s not enough. But, what does that mean for you? How do you decide if you should be applying ESG strategies to your stock market investments?

If you're a person who disagrees with our current economic system, let me reiterate that I think the first step is to seriously think through whether you want to be investing in the stock market at all (as I discussed here). I mention this again because IF you choose to invest some of your savings in the stock market, your personal reasons for doing so will probably play a key part in framing how you want to think about ESG.

If you determine that you are going to hold some stock market investments, then I think the next question to ask yourself is: do I want to pay the additional costs required to apply ESG to these investments?

I’ve noticed that this additional-cost-question is often glossed over in discussions about ESG. I believe this is a mistake. Let me explain.

ESG strategies generally fall into one or more of these three categories:

- Negative screens - screening out certain types of “bad” companies that you don’t want in your investment portfolio, such as companies whose primary business is in fossil fuels, weapons, private prisons, etc.

- Positive screens - actively identifying and “screening in” certain types of “good” companies that you want to have more of in your portfolio, like green energy companies.

- Shareholder engagement - using the fact that you hold shares of a company as a way to try to influence the company to pursue ESG goals. Shareholder engagement examples include voting on matters brought to shareholders (proxy voting), submitting shareholder resolutions, or speaking directly with the company leaders as a shareholder.

To be done well, all of these strategies have costs.

Investing Costs 101 Explainer

Financial intermediaries: Most people do not hold individual stocks directly, rather, they are invested via financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries can include financial advisors, 401K and other retirement fund managers, mutual fund or ETF portfolio managers, and a wide array of asset managers that are often employed by these other intermediaries. Financial intermediaries have come to play an enormous role in how Americans relate to the stock market today, particularly when it comes to investment decision-making for retirement savings goals. While definitions vary, in this article I use the term “financial intermediary” to refer to any person or entity that sits between you and your investment portfolio in the investment decision-making and management process. These people and entities charge you, the end investor, various management fees for the services they provide.

Active vs Passive investing strategies: “Active” investing refers to strategies that involve stock picking where the asset manager makes active choices about which stocks will be “winners” relative to others and positions an investment portfolio accordingly. The goal of active management is to deliver higher returns than the overall market or than a comparable benchmark if the portfolio is focused on a specific subset of the market. “Passive” investing refers to investing strategies that attempt simply to match the market, without taking any stance on which stocks will be winners or losers. Passive strategies are achieved by creating portfolios that match an index of all companies in a given category of the overall market. For example, a passive fund may match an index of all S&P 500 companies, or it may match an index of all publicly-traded U.S. companies of a certain size. Passive management strategies require less management work, and therefore typically cost much less than active management strategies. Passive strategies have also been shown to historically deliver better long-run returns than active investing strategies on average. Still, the value of passive vs active approaches continues to be a heated debate within the investment world today. When considering this debate, it’s worth remembering that, as with all things in the stock market, past trends do not guarantee future results.

Mutual Funds vs ETFs: A common way to hold a broadly diversified portfolio of stock market investments today is via mutual funds or ETFs. Both mutual funds and ETFs are vehicles for investors to get diversified exposure to some or all of the stock market by pooling their money with other investors to buy a “basket” of stocks (or bonds or other traded securities). Both mutual funds and ETFs can use either an active or a passive management approach (note: some people mistakenly assume all mutual funds are actively managed and all ETFs are passively managed, but this is not true). Mutual funds that are passively managed to match a specific index are usually called “index funds.” The main differences between mutual funds and ETFs is in how they are valued and how you buy into them. You have to actually “buy into” a mutual fund and the value of your mutual fund shares will always match the value of the companies held in the mutual fund portfolio at the end of each trading day. ETFs - which stand for “exchange traded funds” - are traded as stocks themselves, so their price is determined by what the market is paying at any given moment for the ETF, not necessarily what the underlying stocks within the ETF are worth (although theoretically these should be similar). Many people associate ETFs with extremely low management costs. It’s true that ETFs do often have lower costs than mutual funds, but there are also some passively managed mutual funds with lower costs than many ETFs.

Understanding Asset Management Costs: The main way to evaluate the costs of investment management intermediaries is to look at expense ratios. All mutual funds and ETFs have expense ratios. Other intermediaries involved in managing your investments - like your 401K or IRA manager, your financial advisor if you have one, or even your robo-advisor if you use that, likely also have expense ratios associated with them. The expense ratio is calculated as an annual percentage of all investment management costs and fees relative to the total assets under management (AUM). For example, an expense ratio of 0.5% would mean that for every $100,000 you have invested via this intermediary, you are paying $500 per year for management costs associated with that $100,000. Expense ratios are also often cumulative. Say you use a robo-advisor with an expense ratio of 0.3% to manage your portfolio and you are invested in a mutual fund that has an expense ratio of 0.4%. This means you would be paying a total expense ratio of 0.7% or $700 per year for every $100,000 invested.

In some cases, particularly with mutual funds and ETFs, you might never see these expenses “coming out of” your portfolio. Instead, your returns each year are simply reduced by the amount of the expense ratio. So, for example, if your total expense ratio on your portfolio is 1% and the portfolio returns 7% in a given year, you would get a 6% return that year. While they can seem opaque and hidden, these expenses can matter A LOT because you pay them annually whether the market is up or down, and because they get compounded over time. There are parts of the finance industry that are kind of obsessed with this issue of how much management costs can reduce investors’ returns. This has driven a huge demand for products with very low expense ratios and has led to an enormous inflow of funds into passive investing strategies over the past few decades.

A few comments about the focus on low expense ratios: I completely agree that it is important to pay attention to asset management costs so that people are not deceived about what they are paying and to put pressure on the finance industry not to charge more than is appropriate for their management services (whether this is working is debatable). There are some cases, though, where I think this obsession with low fees may be going too far. The thing about investment management is that the costs don’t change very much as your assets under management grow. So, if you are managing an enormous amount of assets (like say you’re BlackRock, Vanguard, or State Street who collectively manage $22 trillion in assets, equivalent to almost half the value of the U.S. stock market), you can charge extremely low expense ratios and still make lots of money. However, if you are a smaller asset management firm attempting to thoughtfully apply ESG strategies, your relative costs are going to be higher both because your AUM (assets under management) is smaller and because you are providing more services for your investors.

Among other concerns, I believe this obsession with extremely low expense ratios can play a gatekeeping role in keeping newer investment funds run by diverse managers from getting a foothold in the industry. Today, only 1.4% of U.S.-based assets under management are managed by firms owned by women or people of color. I don’t know about you, but I don’t see any way an “environmental, social, and governance” movement can be effective if it is 98.6% reliant on the leadership of wealthy white men for its success!

Now, let me return to my earlier point: I think we should be clear about the fact that applying ESG to an investment portfolio will cost more than many of the lowest-cost passive investing options out there.

As I mentioned, doing ESG involves some combination of negative screens, positive screens, and shareholder engagement. If you are doing negative screens, some person or entity (or you) needs to determine what screens to apply. They also need to administer those screens while still keeping your portfolio otherwise “optimized” for the best long-term returns. If you are doing positive screens, you need people and resources focused on identifying the best companies in any given sector. Part of positive screening involves ensuring not only that a company’s goals and financials align with your screens, but also that the stock price valuations are reasonable so that you can expect to make a return over the long run. If you are doing shareholder engagement, you also need people and resources dedicated to voting your proxies for every company you hold, staying in communication with companies, and coordinating with other organizations working to advance ESG goals.

For these reasons, I believe we should think of “doing ESG” as an extra service we can choose to pay for, that goes beyond standard passive investment management services. (Am I saying that by paying more you can be certain you are getting good ESG services? Definitely not. I’m just saying that not paying anything for ESG is a pretty good sign you are not actually doing ESG.)

Deciding if you want to pay for ESG

Now let’s talk about how you might assess whether the cost of ESG is worth it to you.

I’d like to suggest that one of the first factors you’ll want to consider here is where you - and your family, if applicable - fall along the wealth distribution spectrum. Specifically, do you fall in the top 10% or the bottom 90% of wealth holders? (Here, I’m referring to the distribution of wealth in the U.S, but many other countries have similar wealth distribution dynamics).

As I’ve discussed previously, the cut-off for being in the top 10% of U.S. households by wealth is approximately $1.3 million in net household assets ("net assets" means everything you own minus everything you owe). Generally speaking, if your household has more than $1.3 million in net assets, you are in the top 10%. And, if your household has less than $1.3 million in net assets, you are in the 90%. Of course, it’s not that simple, and if you feel you are on the line between the 90% and 10%, you will have to determine for yourself which category is most relevant to you. My point is not that these are precise categories, but rather that they are very important general categories to consider due to the shape of wealth distribution in the U.S. today.

Why do I think your wealth distribution category matters so much in the context of making decisions about ESG within your own portfolio?

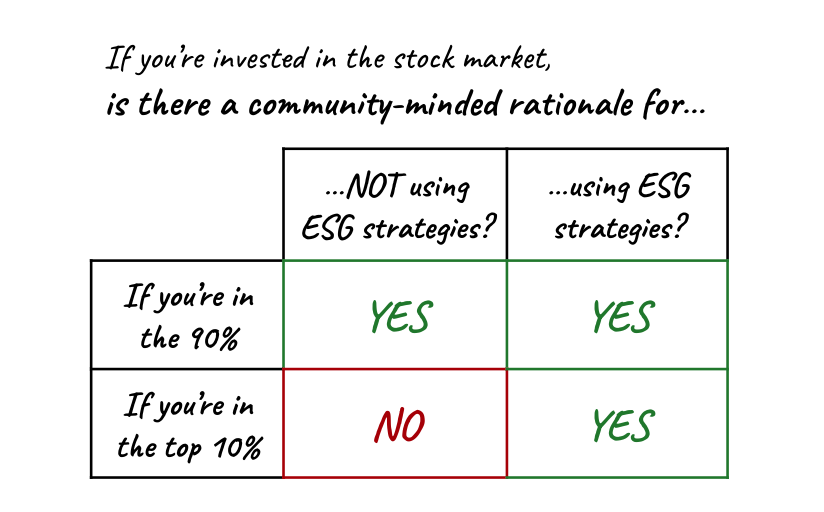

My thoughts on this are summarized by the below diagram:

In the remainder of this article, I’ll attempt to explain my thinking related to each section of this matrix.

If you’re in the 90%, rationale for NOT doing ESG

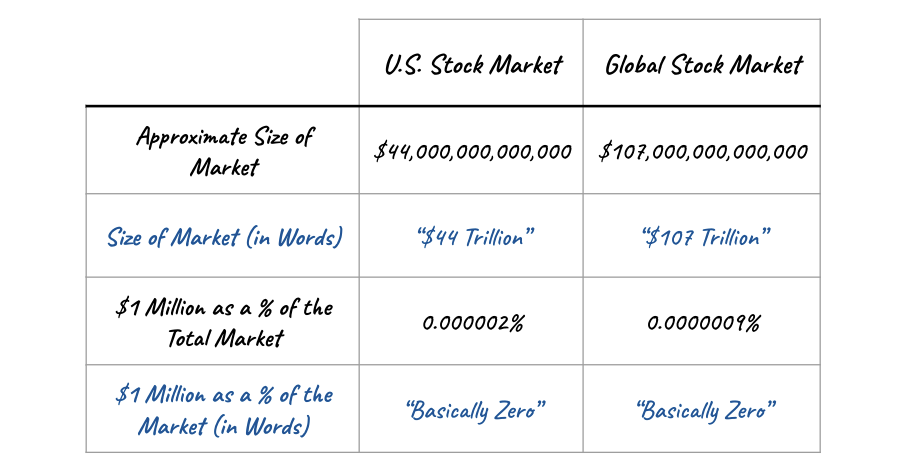

If you are in a household that falls in the 90% category, let me just tell it to you straight: the stock market could not care less about what you do. Remember, the 90% collectively owns only 11% of the stock market. If you are in the 90%, it’s worth being clear about the fact that your investments are no more than a speck of dust on the “beast” that is the public equities market.

Even if you have, say, a million-dollar portfolio invested in the stock market, here’s how the numbers look:

You can try to “stab at the beast” by screening out or divesting from certain companies. You can try to “direct the beast” by voting your proxies or participating in other forms of shareholder engagement. Or, you can choose to just “ride the beast” by not using ESG strategies at all. Does the beast care what you do? I’m sorry to break it to you, but it does not.

This would be the main argument for not choosing ESG strategies if you are in the 90%. As we’ve discussed, ESG strategies cost money. Say you are comparing a fully passively managed fund to a fund that includes ESG strategies. From what I’ve seen, you can expect to pay about 0.8% more for a well-managed ESG fund that actively screens out bad companies and does strategic shareholder engagement. So, for every $100,000 you have invested, you can expect to pay about $800 extra per year to apply ESG to your savings.

Since you are in the 90%, you likely face some very real trade-offs and constraints with your financial resources, so you may determine that this extra cost per year (about $800/year if you have $100,000 invested or $8,000/year if you have $1 million invested) is better spent elsewhere. What a better use of that money looks like is a personal decision, but it could certainly include supporting efforts focused directly on getting to that Line (C) - A Just and Regenerative Economy - from my diagram above. You could argue that such a choice would be a more impactful use of these dollars than paying a financial intermediary to apply ESG to your speck of dust in the public equities market.

If you’re in the 90%, rationale FOR doing ESG

But please don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying you definitely shouldn’t do ESG if you’re in the 90%. I’m just saying I can see a coherent case for why you may weigh your options and choose not to, even if you are taking a community-minded approach to your finances. On the other hand, you may also consider the issue and determine that the cost of ESG strategies is worth it to you.

There’s no denying it. If you’re a person who has a community-minded perspective and you are invested in the stock market, applying at least some form of ESG to your portfolio is likely going to feel a lot better than not. Even with the knowledge that, say, screening your portfolio of investments in private prisons is going to have no impact on those private prison companies, you may still determine that it’s worth it to you to pay a little extra to know you don’t hold the “worst of the worst” of publicly traded stocks. This is also a totally coherent rationale.

Additionally, you might like that by doing ESG, you can direct some of your management fees to entities that may share more of your values than traditional asset management firms. Many of us make choices in various parts of our lives to pay a little bit more for things that just feel better to us for any number of reasons. You may consider the additional cost of applying ESG to your portfolio to be in line with the value you gain from the feeling of having a “geener” portfolio managed by an entity that at least purports to care about things you care about. Furthermore, it may also be worth it to you to pay a little more to signal your preference for ESG, on the theory that this can influence public opinion and therefore indirectly influence companies to care more about ESG causes.

These are all good reasons!

My point is that it's important to be clear that, if you’re in the 90%, this is NOT like voting. This is not like the choice to eat less meat. This is not like the choice to buy local. This is not like the choice to bike vs drive. Because of the massively skewed way that wealth is distributed today in the U.S., your decisions about whether or not you apply ESG to your stock market investments - if you have them - are way less impactful than how you vote, what you consume, and other decisions you can make where you can have a relatively similar amount of impact regardless of your wealth level.

I think you should definitely make the choice to pay for ESG for your stock market portfolio if that feels right to you. But please do this because the feeling is worth it to you. Do not do this as a strategy to “make the world a better place” if you’re in the 90%.

(Please note: I do not believe this point holds about any investment you make if you’re in the 90%. Even small investments can have a significant impact if, for example, you are making local direct investments or other community-based investments. I will be returning to this point in future posts.)

If you’re in the top 10%, rationale for NOT doing ESG

In contrast to the 90%, if you are in the top 10% of wealth holders and do not agree with our current economic system but still choose to be invested in the stock market, I honestly can’t think of a moral rationale for not using ESG strategies with your stock market portfolio.

If this happens to describe you, please understand that I am not saying that you are not a moral person. It is extremely likely that you are in this position because of the many layers of intermediaries (401Ks, mutual funds, financial advisors, etc) between you and your investments. All these intermediaries may be managed by good people all doing their jobs well based on the consensus assumptions of their professions. They are just swimming with the stream of what is considered industry best practices and you, reasonably, have been trusting them as the professional experts that they are.

But, the problem is that this “stream” made up of consensus assumptions within the finance industry has become morally eroded. Because of the extreme forms of extraction that have become status quo in our finance industry today, there is no way to swim with the stream and not be part of environmental destruction and human exploitation. ESG has come to be the catch-all category for any investing strategy that attempts to be a little bit less anti-human and a little bit less anti-environment. Since it’s there and it’s becoming a real viable option, once you realize this, I can’t think of a clear moral reason (tactical reasons, yes, but not moral) for not doing some form of ESG if you choose to be in the stock market and you are in the top 10% of wealth holders.

My main case here is that, unlike the 90%, as a member of the top 10%, there is no risk that paying a little extra for ESG will make or break your ability to meet your basic needs. And, unlike the people in the 90%, what you do with your investments matters significantly more than the average person.

If you are in the top 10% but not in the top 1%, you may be thinking, well, I’m also still just a speck of dust to the market. Maybe a slightly larger speck of dust than people in the 90% but still minuscule to the market. To that I would say, this is a fair point, and… remember this: if you have $1.3 million in net assets, you have over 50 times more assets than the median Black household in America. So while it may not feel like that much relative to the 1%, it’s exponentially more than most Americans. Ignoring this is not being honest about your relative privilege and associated responsibilities if you disagree with our current economic system.

If you’re in the top 10%, rationale FOR doing ESG

I hope I'm making it clear that arguments that take a your-investments-don’t-matter-in-the grand-scheme-of-things angle, may hold for people in the 90%, but they fundamentally don’t hold for the top 10%.

If you take only one thing from this article, I hope it’s this: be VERY skeptical of advice about whether your investment choices “can make a difference” that lumps investors of all wealth levels together as a single category. I hope you can see that this common practice of grouping all investors together can be used as a strategy to manipulate you.

To recap, here’s how that manipulation can work:

- Sometimes we hear that, from a systemic perspective, "your stock market investment choices DON’T matter." This argument has some validity if you’re talking only about the bottom 90% of wealth holders. However, it is often used by the top 10% to avoid taking responsibility.

- Other times, we hear that "your stock market investment choices CAN make a difference." This argument makes sense for the top 10% of wealth holders who collectively hold 89% of the stock market. But, it is often used as a way to justify charging people in the 90% more for financial services. (And, possibly, as a tactic to distract people in the 90% from engaging in more effective strategies for pursuing systemic change.)

If you’re in the top 10% and you disagree with our current economic system and you still choose to be in the stock market, there’s a clear case to be made that you are among a relatively small group of people whose stock market investment choices actually could make a difference.

In your case, I think a community-minded approach would suggest not just that you apply ESG to your portfolio, but that you put some time and resources into ensuring it is done well.

Getting started with ESG

This article is already far too long for me to also cover the topic of how to do ESG well. But, let me at least leave you with a few thoughts about how to get started with doing ESG well.

As I see it, to do ESG well with your investments, either you, your intermediaries, or (ideally) both, will need to put in time and resources dedicated to actively swimming against the stream of the finance status quo.

Without this dedicated focus, your investments WILL be upholding environmentally and socially destructive activities.

Because most people do not directly manage their investment portfolios (at a minimum, most people rely on ETF and mutual fund intermediaries), I’m going to focus here on how you might want to think about assessing financial intermediaries doing ESG. What you’ll want to determine is who are the financial professionals or entities who are doing more than just superficially adding ESG labels to otherwise status quo finance practices.

How do you identify who is actually actively swimming against the stream of the finance status quo?

There is no single simple answer but, importantly, let's recognize that the answer to this question is as much an art as it is a science. Exactly what it means to "swim against the stream of the finance status quo" is subjective and will vary from person to person. This is a good thing and part of what it means to participate in systemic change! And, it also means that it’s especially important that you personally engage enough to make an assessment yourself, ultimately based on your own intuition, about any financial intermediaries you choose to work with to implement ESG for your portfolio.

Here are some elements to look for as you make this assessment:

- Transparency - does the financial professional or entity have mechanisms to clearly show you exactly what companies you are holding and why?

- Clarity of approach - can the person or entity clearly explain their investment management approach and how it is similar and different from industry standard approaches?

- People of color and women in leadership positions - how diverse are the teams with decision-making power over your investments?

- Evidence of engagement with companies - how does the person or entity engage with companies on your behalf as a shareholder? Can they transparently explain their proxy voting policies and other ways they engage to influence companies?

- Evidence of collaboration with others - how are they collaborating with other players inside and outside the finance industry to work together to change the direction of the “stream” of current finance business-as-usual?

If you look, you can absolutely find financial advisors, mutual funds, and even ETFs that reasonably meet these criteria. You can also find many, many others that are just ESG marketing with no substance. The truth is, there is no way you can discern what’s what without putting in some time to engage and research and then, at some point, trusting your gut.

It’s my opinion that, if enough people (in the top 10%) made it a priority to ensure their stock market portfolios were managed in a way that passed their personal gut check for "swimming against the stream of the finance status quo," maybe ESG could help nudge the needle toward a better future.

And, as you may not be surprised to hear, I also think there are many areas outside of ESG and the stock market where our investment decisions can have significantly more impact. In this case, I'm talking about investments made by both the top 10% and the 90%! If you're interested in this, please stick around. I intend for this to be the focus of most of my future articles in these pages.

Footnotes:

[1]

I’m trying to make clear that I use ESG to refer exclusively to investing approaches to publicly traded corporate securities. That is, when I say "ESG," I’m talking about strategies for investing in what I’ve been calling “stock market” companies or “Wall Street” companies. I consider other mission-related investing strategies outside of public markets to be OUTSIDE the umbrella of “ESG.” For example, I consider community investing to be a different category altogether from ESG. Furthermore, when I say ESG, I’m not talking about recent trends of “ESG alternatives” like so-called “ESG PE firms” or “ESG venture capital.”

[2]

Of course, certain parts of our world are already in collapse, so yes, I acknowledge that this diagram is ridiculously simplistic and generalizing. As I said, I had to brush over a lot of nuance in the interest of article length...

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.